Pilot project could allow kids to receive high-quality overnight sleep assessments in the comfort of their own beds

While sharing a room on a vacation, Finn’s family noticed something unusual with the way the toddler slept. He snored loudly, slept with his mouth wide open, and changed positions constantly throughout the night. He would also complain of being tired after a full night’s rest—not to mention a three-hour nap. Finn’s grandmother, a pediatric nurse, suspected that the culprit was enlarged adenoids.

That hunch turned out to be right. Months later, Finn received specialized care at BC Children’s Hospital that consisted of a nasal steroid and then an adenoidectomy, a routine procedure to remove the adenoid glands in his throat.

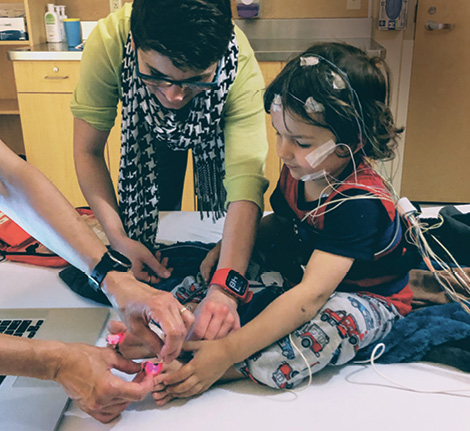

Still, his symptoms persisted. Finn’s medical team at BC Children’s decided to schedule a sleep assessment, called a polysomnogram (PSG), to find out what was going on. So his mom, Denise, packed an overnight bag and the two made the trip from Squamish to BC Children’s. Around 8 p.m., the four year old was hooked up to a multitude of sensors that measured his brain waves, heart rate, movements and more as he tried to doze off.

While considered the gold standard for sleep assessments, PSGs do have limitations. For one, it can be difficult for a child to fall asleep in unfamiliar environments, making it hard to assess the very thing they are there to have examined. The cost and time spent travelling can also be a huge burden for families who live far away. But most importantly, the wait for these assessments is often significant. It’s little surprise: BC Children’s is home to the province’s only pediatric sleep lab.

Finn getting ready for his sleep assessment

Now, a new solution is in the works. BC Children’s Hospital Foundation is currently raising funds to help the hospital’s sleep experts pilot a new research program that could allow kids to receive high-quality overnight sleep assessments in the comfort of their own beds. It would be the first of its kind in Canada.

The Sleep Lab at Home program could offer a host of benefits. It would minimize disruption in families’ lives, reduce waitlists, and help improve the quality of a child’s sleep as they undergo assessments—something that would also improve the quality of data collected.

Finn’s parents were fortunate to participate in an initial pilot of this research program. After Finn’s assessment, health care providers continued to monitor their son’s sleep patterns through the pilot Sleep Lab at Home program. Results from the PSG revealed that Finn was still snoring and experiencing obstructed breathing—but ultimately, doctors decided that he didn’t require any further treatment as he was growing and the lymphatic tissue in his throat was shrinking, creating more space for breathing at night.

The possibilities of this model extend well beyond sleep assessments. If successful, it could be replicated and expanded into countless areas of health care—for example, monitoring kids after lowrisk surgeries so they could return home sooner.